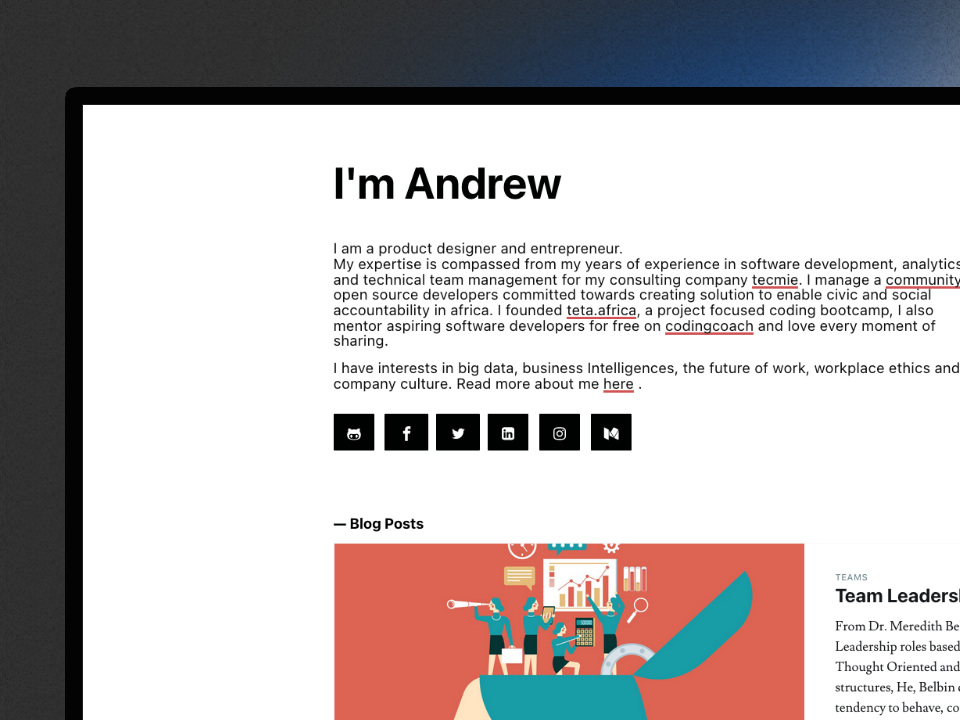

From WordPress to Jekyll: Rebuilding My Digital Home

Every personal website is a time capsule. I have rebuilt mine so many times that you can read the layers like a timeline, both for the web and for how I write.

The Early Days: Jekyll + Tachyons on Netlify

The first real version of this site ran on Jekyll with the Tachyons CSS framework, deployed to Netlify. It was simple, fast, and version-controlled. I wrote in Markdown, pushed to GitHub, and Netlify rebuilt the site automatically. There were earlier experiments too: Bourbon and Donna were previous incarnations, each one a snapshot of whatever CSS approach I was excited about at the time.

The workflow was elegant, but after a while writing Markdown in a code editor felt like more code on top of the code I was already writing all day. I wanted a real editor, a place to draft ideas, rearrange blocks visually, and publish without touching a terminal.

The WordPress Years: Bedrock on DigitalOcean

So I switched to WordPress, specifically the Bedrock stack, hosted on DigitalOcean with MySQL. Bedrock gave me the Git-based workflow I wanted: plugins and themes managed through Composer via WPackagist, configuration in environment variables, and a clean separation between WordPress core and my customizations.

The Gutenberg block editor sealed the deal. The WordPress team did genuinely impressive work on the editing experience. I could draft things in chunks, embed code blocks with syntax highlighting via the Code Block Pro plugin, drop in images, and publish when ready. It felt like the right tool for someone who wanted to write rather than build.

And it worked. For a couple of years, I published regularly. The site accumulated 429 pages of content spanning blog posts from 2012 to 2025, a portfolio of experiments, talks, and what would eventually become a digital garden.

But WordPress carries weight. The database. The hosting. The plugin updates. The PHP runtime. The attack surface. Every time I wanted to make a design change, I was fighting a theme system that wasn’t built for the kind of precise, utility-first styling I had grown used to. And the Gutenberg output, while great for writing, produced HTML that was heavy with wrapper divs, inline styles, and WordPress-specific class names.

Then traffic started growing. What used to be a manageable trickle of visitors turned into consistent daily hits that pushed the DigitalOcean droplet to its limits. I found myself needing to upgrade the server just to keep the site responsive under load. For a personal blog. WordPress was doing dynamic page rendering, querying the database, and executing PHP on every single request. It felt absurd to be scaling infrastructure for what is fundamentally a collection of static documents. That was the final nudge. If I’m going to pay for more compute, I’d rather pay for none at all.

Setting Up the Starter

Before touching any WordPress content, I set up the destination: a clean Jekyll 4.4 project with Tailwind CSS 3.4, the Typography plugin, and PostCSS wired through jekyll-postcss-v2. This meant getting Ruby versions, Bundler, and npm modules all playing nicely together, making sure Gemfile.lock had the right platforms for deployment, that the PostCSS pipeline worked without cssnano (which has a css-tree incompatibility), and that the build actually produced output before any content went in.

This was deliberate. The bulk of the real work in this migration was two things: wget --mirror to capture the source, and getting the Jekyll + Tailwind starter into a deployable state. Everything else, the actual content migration across 429 pages, turned out to be the easy part, but only because the foundation was solid first.

The Migration: 429 Pages, One Python Script

The migration started with a question: what if I just wget the entire site and work from there?

That’s essentially what happened. I used wget --mirror to create a static HTML clone of the WordPress site, all 429 HTML files of it. But here’s the thing about WordPress: most of those pages aren’t actual content. They’re the taxonomy and archive cruft that WordPress generates automatically. The extraction script’s first job was filtering all of that out:

andrewmiracle.com/ ← 429 HTML files from wget --mirror

├── 2012/…/slug/ ✓ blog posts (YYYY/MM/DD/slug)

├── 2019/…/slug/ ✓ blog posts

├── 2023/…/slug/ ✓ blog posts

├── 2025/…/slug/ ✓ blog posts

├── lab/slug/ ✓ portfolio experiments

├── garden/slug/ ✓ digital garden notes

├── talks/slug/ ✓ presentations

├── whoami/ ✓ special page

│

├── category/programming/ ✗ taxonomy archive

├── category/ai/ ✗ taxonomy archive

├── tag/docker/ ✗ taxonomy archive

├── tag/llm/ ✗ taxonomy archive

├── author/andrew/ ✗ author archive

├── page/2/ ✗ pagination

├── page/3/ ✗ pagination

├── feed/ ✗ RSS/Atom feeds

├── wp-json/ ✗ REST API endpoints

├── wp/wp-admin/ ✗ WordPress admin

├── cdn-cgi/ ✗ Cloudflare routes

├── app/ ✗ WordPress app routes

└── portfolio-category/ ✗ portfolio taxonomy

Roughly half the mirrored files were category listings, tag archives, paginated index pages, and WordPress infrastructure routes, none of it actual content. After discarding those, the BeautifulSoup-based parser classified the remaining pages by URL pattern: anything matching YYYY/MM/DD/slug became a blog post, lab/slug became a portfolio item, and so on. Frontmatter was extracted from Open Graph and article meta tags. Content was pulled from the div.post-content area between the entry header and article footer.

Images were the tedious part. The script preferred data-src over src for lazy-loaded images, stripped WordPress’s ?resize=...&ssl=1 query parameters, and downloaded everything to local paths under assets/images/uploads/. Hundreds of images, each one needing to resolve correctly.

The 8GB Image Problem

Then came the unpleasant surprise. The downloaded uploads/ directory weighed in at over 8GB. For a personal blog. The culprit was WordPress’s thumbnail regeneration system. Every time you upload a single image, WordPress generates multiple resized copies: a 150x150 thumbnail, a 300-wide medium, a 1024-wide large, plus any custom sizes registered by the theme or plugins. A single 2MB photograph would spawn 5-6 variants with filenames like headshot-150x150.jpg, headshot-300x200.jpg, headshot-1024x683.jpg. Multiply that across hundreds of uploads over several years and the bloat is staggering.

The fix required a dedicated cleanup script that worked in three passes:

- Rewrite references: scan every content file for image paths containing WordPress’s

-NNNxNNNdimension suffix and rewrite them to point to the original full-size file instead - Promote orphans: when a thumbnail existed but the original was missing (WordPress sometimes only kept the resized version), copy the thumbnail to the original filename before rewriting

- Purge the rest: delete every remaining file matching the

-NNNxNNNthumbnail pattern, then clean up empty directories

The assets/images/uploads/ directory went from 8GB down to a fraction of that. Every image on the site now references exactly one file, the original, with no redundant WordPress-generated variants cluttering the repository.

But the static HTML clone only captured what was published. WordPress keeps drafts, revisions, and unpublished content locked inside its MySQL database. So I exported the full SQL dump and wrote a second parser to walk the wp_posts table, pulling out every draft, pending, and privately published post alongside their metadata from wp_postmeta. This gave me a full picture of how content was structured on the WordPress side: which posts were drafts I had abandoned, which were works in progress worth finishing, how categories and tags were assigned, and what the internal linking patterns looked like. It was basically an audit of years of accumulated writing, surfacing things I had forgotten I started.

The result: 181 blog posts, 23 lab projects, plus special pages like the garden, talks, and about page, all with clean Jekyll frontmatter and the original HTML content preserved. The drafts from the database export became a backlog of ideas to revisit in the new system.

Jekyll + Tailwind: The Current Stack

The new site runs on Jekyll with Tailwind CSS 3.4 and the Typography plugin. No database. No server. Just files, folders, and a build step.

The type system uses four fonts: STIX Two Text for headings and prose, Noto Sans for body text, Shantell Sans for navigation elements, and Intel One Mono for code. STIX won out over Montaga, Sedan, and Newsreader after I tested all four side-by-side. I wrote up the full comparison in a note on exploring serif fonts. STIX isn’t the most exciting choice, but it’s the only one that works everywhere: headings, body, captions, footnotes, without compromise. For a site that’s part garden, part portfolio, part blog, flexibility wins over flair. Syntax highlighting is handled client-side by Prism.js with the Tomorrow Night theme and an autoloader that fetches language grammars on demand.

Content is organized as collections: _posts for the blog, _lab for experiments, _garden for the digital garden (with growth stages: seedling, blossoming, flourishing), and _talks for presentations. Posts with code blocks have been rewritten from WordPress’s heavy inline markup to clean Markdown with fenced code blocks.

The site builds in under 3 seconds, deploys on push, and scores well on every performance metric that WordPress made me fight for.

Debugging Is Just Reading HTML

One thing I didn’t anticipate but now consider a major advantage is that debugging a Jekyll site is absurdly straightforward. When something looks wrong, a broken layout, a missing image, a Liquid tag that isn’t resolving, you don’t need to trace through PHP templates, query a database, or inspect WordPress’s layered theme hierarchy. You just run bundle exec jekyll build and open the generated HTML file in _site/.

The output is right there. Plain HTML. If a post’s frontmatter is malformed, the rendered page will show it. If a Liquid loop is iterating over the wrong collection, the HTML output makes it immediately obvious. If a Tailwind class isn’t being applied, you can inspect the built CSS to see whether the class was purged. Every bug becomes a matter of comparing what you wrote in the source with what appeared in the output. There is no black box between input and result.

With WordPress, debugging meant toggling plugins on and off, checking wp_options for misconfigured settings, reading PHP error logs, or worse, dealing with issues that only appeared on the live server because your local environment had a slightly different PHP version or MySQL configuration. The feedback loop was long and indirect.

With Jekyll, the feedback loop is simple: write, build, read the HTML. That’s it. The _site/ directory is the entire truth of your site. When you pair that with browser DevTools, you can diagnose and fix virtually any layout or content issue in minutes rather than hours. It’s the kind of simplicity that makes you wonder why you ever tolerated anything more complicated.

A Vercel Deployment Gotcha

One thing that tripped me up when deploying to Vercel was that the build kept failing with cryptic Bundler errors. The culprit turned out to be a platform mismatch. Vercel’s build environment runs on x86_64-linux, and if you’re developing on macOS, your Gemfile.lock won’t include the Linux-native gem variants that Vercel needs.

The fix is one command:

bundle lock --add-platform x86_64-linux

This tells Bundler to resolve and record the Linux-specific builds of native gems like ffi and sass-embedded in your lockfile. Without it, Vercel’s bundle install can’t find compatible binaries and the build fails before Jekyll even runs. Commit the updated Gemfile.lock and the deploys work cleanly from there.

Why Now: Claude Cowork and the AI-Native Publishing Workflow

Here’s the part that made the timing right. The real catalyst wasn’t dissatisfaction with WordPress, it was the emergence of AI coding assistants that fundamentally changed what “migrating a website” means.

Once the Jekyll starter was solid and the wget --mirror dump was ready, the actual migration, parsing 429 HTML files, extracting frontmatter, classifying content into collections, downloading images, was a single session with Claude Code running Opus 4.6 in plan mode. One shot. I described the source structure, pointed it at the HTML dump, and it produced the extraction script, the image cleanup pipeline, and the frontmatter mapping in one continuous run. The kind of task that would have taken a weekend of scripting and debugging took an afternoon of reviewing output.

That’s the thing about AI-assisted development that’s hard to convey until you experience it: the bottleneck shifts. The hard part wasn’t writing the migration code, it was the preparation. Getting the starter right, ensuring Ruby and Node compatibility, choosing the right fonts, setting up the deployment pipeline. The unglamorous foundation work that no AI can shortcut because it requires taste and context. Once that was in place, the mechanical work of migrating 181 posts and 23 lab projects was almost trivial.

With Claude Cowork from Anthropic as a coworker in my editor, the old friction of static site publishing has disappeared too. I can dump my thoughts completely unstructured, raw notes, half-formed arguments, bullet points mixed with full paragraphs, and Claude helps me shape them into publishable prose. The workflow now:

- I write messy, stream-of-consciousness notes in a Markdown file

- Claude helps me restructure, polish, and fact-check

- I review, adjust voice and emphasis, and commit

- Git push. Site rebuilds. Done.

This works because Jekyll uses folders, collections, and Markdown to organize the site hierarchy. Everything is a file. Every file is readable. An AI assistant can understand the entire site structure by just looking at the directory tree. It knows where posts go, what frontmatter fields are expected, how images are referenced, and what the permalink structure looks like. Try getting that kind of structural legibility from a WordPress database.

The combination of Jekyll’s file-based architecture and AI-assisted development has given me something I haven’t had in years: a publishing workflow that feels faster than thinking. I spend my energy on ideas, not on tooling.

What Stays, What Changes

The content is the same. Every post, every experiment, every image from the WordPress era is preserved at its original URL. Nothing was lost in translation.

What changed is the relationship between me and the site. It’s mine again, in the way that only a repository of plain text files can be. No login screen. No admin panel. No plugin vulnerabilities. Just a folder of Markdown files that I can read, edit, and publish from anywhere, with Claude Cowork making the whole process feel effortless.

If you’re curious about the technical details, the Colophon on my about page has the specifics. And if you’re a fellow WordPress refugee considering the jump to static, I’d say the tooling has finally caught up to the dream.

The web is better when personal sites are weird, fast, and entirely yours.

Continue Reading

The Side Effect of Vibe Coding Nobody Talks About

A subtle shift from AI coding: reading code faster, and why tiny diffs suddenly feel like a slowdown worth unpacking.

Vibe Coding and the Death of Knowing What You're Doing

Andrew Miracle on vibe coding, the blurred line between juniors and seniors, and why nobody cares how the spaghetti w...

The future of work is your Talent vs GPU

Andrew Miracle challenges AI-in-Africa hype, arguing talent without infrastructure leaves growth and opportunity behind.